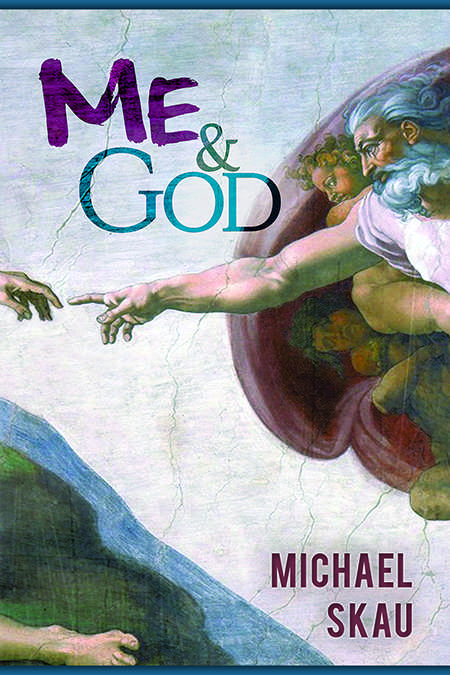

Me & God

by Michael Skau

Wayne State College Press

With a book title like Me & God, you might expect ambition, even a critique, if not irreverent humor from the colloquial "Me" (and placing it before God) and the cover. And you'd be partially correct. The poems, which should appeal to readers of Billy Collins and anyone who ponders religion, point up the humor ("When angry, he projected/his voice in surround sound" from "Muse"). However, overall, it isn't cruelly or vindictively irreverent. In an interview with Laura Madeline Wiseman, Skau states:

With a book title like Me & God, you might expect ambition, even a critique, if not irreverent humor from the colloquial "Me" (and placing it before God) and the cover. And you'd be partially correct. The poems, which should appeal to readers of Billy Collins and anyone who ponders religion, point up the humor ("When angry, he projected/his voice in surround sound" from "Muse"). However, overall, it isn't cruelly or vindictively irreverent. In an interview with Laura Madeline Wiseman, Skau states:As for the use of foils, as my introduction indicates, “The God that I have fashioned for the poems is one whom I have created in my own likeness.” The advantage here is that I can invest the God figure with my own faults and flaws, and this makes criticism of him much easier. The disadvantage is that the poems encompass a God based on myself, a first person speaker (“I” or “me”) also modeled on myself, and I the poet, who is manipulating the other two: the process can be quite schizophrenic. I try to balance the scales here by sometimes giving God the upper hand, sometimes allowing the I or me to undermine God, and sometimes portraying them both as either right or wrong.One suspects the primary model is the Judeo-Christian one, as the cover suggests. Yet the god in this book encompasses good and evil and thus mirrors more of the Greco-Roman gods. Combining this with the above quote creates an intriguing dynamic: Who is truly being critiqued? God or the self? The latter gains more weight if we have an agnostic approach. The reading becomes bifocal--with two simultaneous interpretations.

I don't mean to make the book overly intellectual but stimulating without mental gymnastics on the reader's behalf. The language is as clear as if the poet were addressing the reader directly. In fact, the temptation would be to dismiss it as simplistic. Listen to the poem on the video. More underlies its seeming simplicity.

His stylistic preference is unsurprising as he spent years as university professor teaching the Beats. He has published book-length critical works on Lawrence Ferlinghetti and Gregory Corso.

His poetry is as accessible as work by Charles Bukowski while remaining thought-provoking. In "Pinball" God is racking up the points while Skau's persona is having difficulty:

Finally, I had a good game--Skau wrestles with God over unluckiness ("Pinball" cited above and "A Day at the Races"), troubles ("Soul-Making" and "Entropy": "Nothing/here is perfect, not even me.") and with his persona over ecology, dreams and vain imaginings (" 'I/am not to blame,' he answered,/'for what I do in your dreams.' "--"Dreams"), road rage ("Goodness": "'Because I said so,' he replied,/reminding me again of my mom."), relationships ("Marriage": "Don't/blame me for human mistakes"), etc. The poem "Fire" challenges both God and his persona.

actually just a good last ball--

and turned the score over, but it never

popped for a free game. God had stopped

to watch me play, and I muttered, half

to the machine, "What do you have to do

to win?" God replied, "You can't win

on that machine."

Two of the more poignant works include "After Birth" where Skau's persona wrestles with the destruction of a new puppy born with a defect that will trouble it to its death, perhaps mirroring why God in "Potters" behaves this way:

Most of [God's pots]

were marred in one way or another:

crooked bottoms, ungainly torsos,

crude handles clumsily attached....

Still God fired his pots in the kiln,One of the more fascinating works--possibly his most famous with a classic feel that often delights listeners at readings--is "Wind" from a 1980 issue of Laurel Review. It predates the 2003 Jim Carrey movie, Bruce Almighty, by twenty-three years. Wind lifts the skirts of a woman on the street.

scratching his signature, "I AM,"

into the unbalanced bases.

He never kept his work, giving

away these luckless mistakes, imposing

the gift of responsibility on others.

"Wow," I said to God. "Did you see that?"This elicits belly laughs from the audience, but possibly consternation from a few who might consider it objectifying. Should readers need a counter balance, they should dip into "Gender" where Skau's persona, like Tiresias, gets transformed into a woman and receives cat calls.

Slowed and hampered by the tightened skirt,

she soon let go and resumed her stride.

God turned to me, eyes atwinkle,

and asked, "Want to see it again?"

The targets in this collection vary; the humor is spot on with the right bite; and Skau provokes thought about religion and the self because if you don't believe God exists, who else can you blame? This should tickle the fancy of most readers on both sides of politics and religion except those at the extremes.

"Winter" could have ended this collection. Skau's persona and God saunter across the winter landscape, and the conversation turns to snow angels, Lucifer's sin, pride, and light. It concludes:

God became pithy: "LightAnd then He pelts the persona with a snowball.

is a difficult honor to bear."

No comments:

Post a Comment