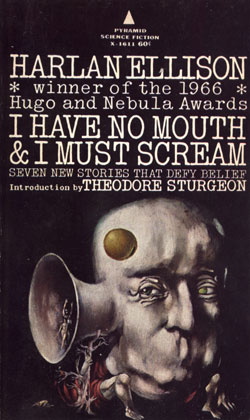

First appeared in If. It won the Hugo and was reprinted in several major retrospectives by Donald A. Wollheim, Terry Carr, Robert Silverberg, Damon Knight, Total Effect, Isaac Asimov, Stephen V. Whaley, Stanley J. Cook, Thomas Durwood, Armand Eisen, Leonard Wolf, Clarkson N. Potter James E. Gunn, Eric S. Rabkin, H. Bruce Franklin, Thomas F. Monteleone, Frederik Pohl, Joseph D. Olander, Patricia S. Warrick, Charles G. Waugh, Martin H. Greenberg, Edel Brosnan, and Peter Straub.

First appeared in If. It won the Hugo and was reprinted in several major retrospectives by Donald A. Wollheim, Terry Carr, Robert Silverberg, Damon Knight, Total Effect, Isaac Asimov, Stephen V. Whaley, Stanley J. Cook, Thomas Durwood, Armand Eisen, Leonard Wolf, Clarkson N. Potter James E. Gunn, Eric S. Rabkin, H. Bruce Franklin, Thomas F. Monteleone, Frederik Pohl, Joseph D. Olander, Patricia S. Warrick, Charles G. Waugh, Martin H. Greenberg, Edel Brosnan, and Peter Straub.Summary:Humanity has been slaughtered an artificially intelligent machine, built to fight WWIII. The last five humans are trapped, immortal but tortured in the belly of the machine. Any time they attempt escape, their fates are made worse.

Analysis:

Despite--or because of--his protestations to the contrary, the narrator is insane (he has to emphasize his own statements which he has not had to do elsewhere):

"I was the only one still sane and whole. Really.

"AM had not tampered with my mind. Not at all."Note, too, that this is written in the past tense, so when we reflect back, it's hard to believe any of his past had much sanity or a lack of tampering. Strange, too, that the five should journey for months and still be inside the machine, with deck plates.

One might question the veracity of his tale, but the story would fall apart. If we were to buy into his narrative, we could understand why he might be insane.

"[D]eath was our only way out. AM had kept us alive, but there was a way to defeat him."The narrator kills his companions to spare them of eternal horror. The computer--as much a creator as the created--transforms the narrator to be stripped of his humanity:

"Outwardly: dumbly, I shamble about, a thing that could never have been known as human."

The title comes into play. Like his creature/creator, the narrator cannot express himself, even his horror, which is what supposedly drove the AI insane:

"We had given AM sentience. Inadvertently, of course, but sentience nonetheless. But it had been trapped. AM wasn't God, he was a machine. We had created him to think, but there was nothing it could do with that creativity."In other words--I suspect--the computer went insane because it couldn't move (or whatever feature that humanity has that the computer cannot have). Stephen Hawking's sanity despite ALS seems to disprove this theory (although maybe Hawking is too intelligent to display his insanity or lacks the omnipotence to destroy humanity and turn the rest of us into slugs, but let's assume he's sane). Moreover, if AM has this incredible omnipotence, yet is trapped in place, wouldn't his powers be enough to simulate movement or create a facsimile of himself that can move?

Also in the above passage, it negates an earlier comparison of the computer to God:

"Most of the time I thought of AM as it, without a soul; but rest of the time I thought of it as him, in the masculine... the paternal... the patriarchal... for he is a jealous people. Him. It. God as Daddy the Deranged."But this machine god does not act like previous gods, but one of pure malevolence. Rather, the interesting part is the masculine aspect. In fact, he describes Ellen's having sex with the men as being "serviced." So perhaps what we hear described is what happens when men become machines.

It's hard not to feel for Ellen. She clings to or favors the man who favors men. Why? Because he presumably does not expect anything from her. She'd taken the narrator twice out of turn, which the narrator refers to with some pride. But this shows a number of aspects in their relationship: She mechanically does each man, presumably to keep them happy. Does it make her happy? The narrator seems to assume so. Four men, one woman. If the reverse were true, presumably the men would be equally pleased.

It's hard not to feel for Ellen. She clings to or favors the man who favors men. Why? Because he presumably does not expect anything from her. She'd taken the narrator twice out of turn, which the narrator refers to with some pride. But this shows a number of aspects in their relationship: She mechanically does each man, presumably to keep them happy. Does it make her happy? The narrator seems to assume so. Four men, one woman. If the reverse were true, presumably the men would be equally pleased.The narrator, however, is jealous of her affection toward Benny and describes her:

"Oh Ellen, pedestal Ellen, pristine-pure Ellen; oh Ellen the clean! Scum filth."It's hard not to imagine this attitude slipping out in tone and/or subtext, even if it were not verbalized. It's at least partially understandable that she is not as fond of the narrator as Benny who was apparently gay. Despite this, for some reason, Benny has been making love with Ellen.

While this theme is critical, it falls behind the Luddite message, or maybe ties into it:

"two great machine with glass-faced dials that swung back and forth between red and yellow lines whose meanings we could not even fathom"Like Ellen, the machine is the thing we cannot fully understand. When we create, we do not anticipate the later repercussions. We create relationships, machines, things we don't fully grasp. We end up down a long, painful road going somewhere we hadn't intended, unable to voice our horrors. Insane.

Ellison was a younger man when he wrote this, which may explain some of the above exaggerated story aspects. Behind closed doors, the technology-positive writers must have disliked the tale.

Ellison's writing is so full of inventive energy--and so admired--that it's strange that more writers didn't follow his lead. Maybe some tried, and their work rebuffed. Instead, the new speculative literature writers followed Brian Aldiss and J. G. Ballard. This is probably due to influential editors like Gardner Dozois, but still surprising that so admired a writer didn't create similar writers.